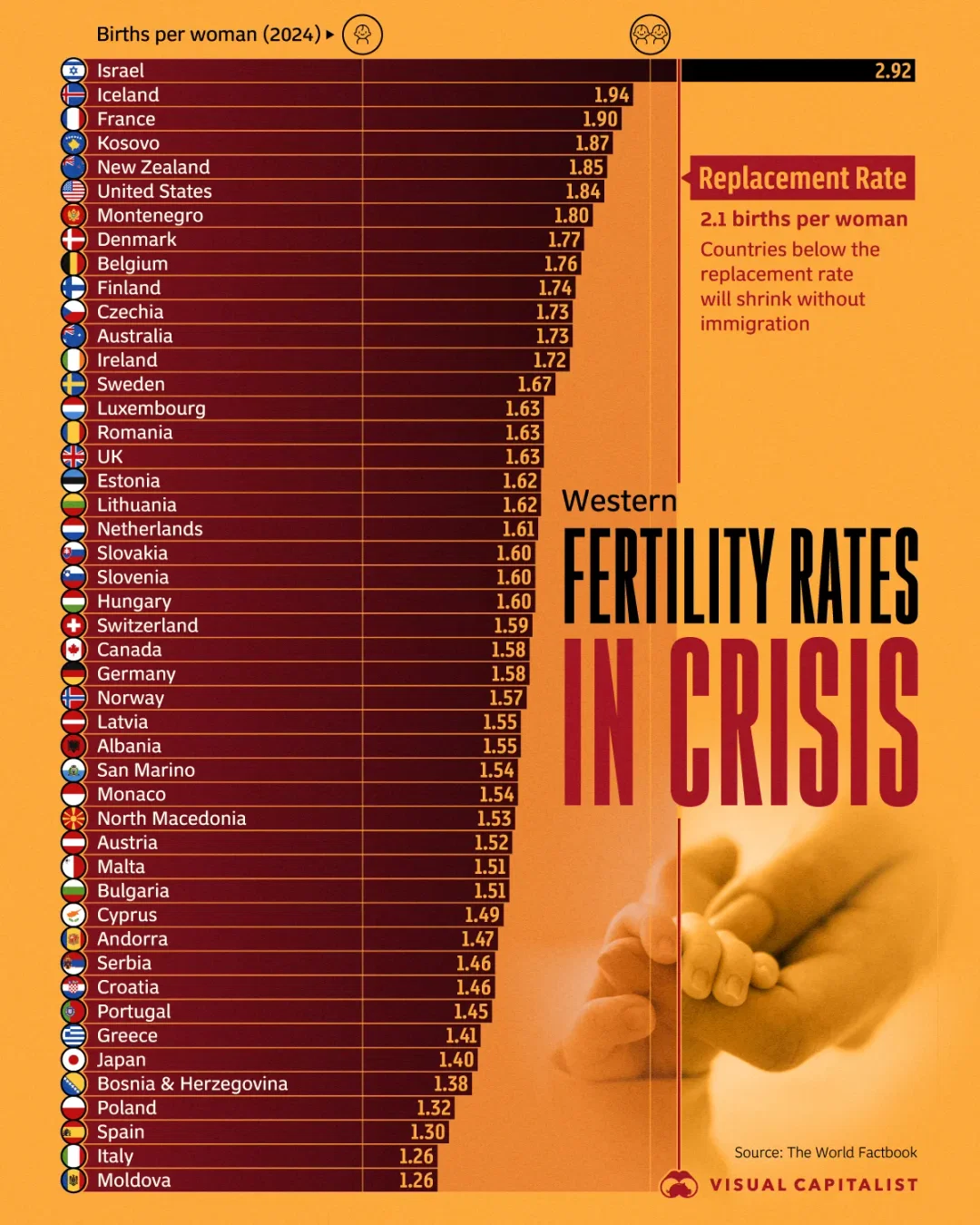

What is fertility rate?

Replacement-level fertility is the number of children the average woman needs to have over her lifetime to “replace” herself and her partner in the population. Because not all children survive to adulthood and because of small differences in male–female birth ratios, this level is slightly above two. In most developed societies with low child mortality, that figure is generally considered to be about 2.1 children per woman. [1]

In contrast, fertility rates across most Western and other high-income countries today are well below this replacement threshold. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the average fertility rate among its member countries has fallen from over 3 children per woman in 1960 to about 1.5 children per woman by the early 2020s. This is substantially below what would be needed for a stable population without migration.

More detailed demographic data show that:

- Europe and Northern America each have total fertility rates significantly below replacement — with Europe around 1.4–1.6 and North America around 1.6–1.8. [2]

- The United States recently recorded a fertility rate of around 1.6 births per woman, below replacement, despite immigration helping to maintain population numbers. [3]

- Very low rates are observed in countries like Japan and parts of Europe, sometimes closer to 1.1 or even below in certain regions. [3]

Among developed countries, Israel is a notable exception, where fertility has remained closer to or above replacement levels, likely due to cultural and social factors that support larger families.

Overall, while global fertility once exceeded replacement levels almost everywhere, today most Western/industrialized nations are below the roughly 2.1 mark, which has important consequences for population aging, labor force trends, and long-term demographic s

The data is both abysmal and obvious [4]

The interaction of economic, cultural, biological, and institutional forces.

Fertility decline in developed societies is not driven by a single factor but by the interaction of economic, cultural, biological, and institutional forces. One of the most consistent drivers is the rising cost of competence. In modern economies, producing a “successful” adult requires far more time, education, and resources than in pre-industrial societies. Children are no longer economic contributors early in life; they are long-term investments. As expectations around parenting rise—education quality, extracurriculars, emotional labor, financial security—families rationally choose to have fewer children, concentrating resources rather than spreading them thin.

- Closely related is the delay of adulthood milestones. In developed countries, people marry later, establish careers later, and achieve financial stability later. Fertility is biologically time-bound, particularly for women, and postponement narrows the window in which children can be had. What begins as “delay” often becomes “foreclosure.” By the time conditions feel safe enough, energy, fertility, or partnership stability may already be declining.

- Another major factor is female labor market integration combined with asymmetric costs. While women’s participation in education and the workforce has expanded dramatically—a genuine achievement—the biological reality of pregnancy and early childcare has not changed. Even in egalitarian societies, women still bear disproportionate physical, emotional, and opportunity costs of childbearing. When career systems reward uninterrupted productivity and penalize absence, fertility becomes a rational casualty. Social policies can mitigate this tension but have not eliminated it.

- Cultural narratives also play a decisive role. Modern societies increasingly emphasize individual fulfillment, autonomy, and optionality over duty, continuity, and sacrifice. Parenthood is framed less as a central life purpose and more as a lifestyle choice competing with travel, leisure, personal growth, and self-expression. When meaning is privatized and responsibility is deferred, reproduction becomes psychologically expensive even when materially affordable.

- Paradoxically, the most gender-equal societies often exhibit the lowest fertility rates. This is not because equality causes infertility, but because high-autonomy environments magnify preference divergence. When individuals are free to choose without economic or cultural pressure, many choose fewer children or none at all. Equality removes coercion—but it also removes inevitability. Fertility, it turns out, is not an automatic outcome of freedom.

- There is also a structural issue of institutional substitution. As states expand welfare, healthcare, elder support, and pensions, families lose their historical role as primary units of security across generations. Children are no longer necessary for survival in old age or continuity of care. This reduces the instrumental necessity of reproduction, leaving only emotional or existential motivations—which are less universally compelling.

- Finally, there is a deeper, often unspoken factor: declining belief in the future. Fertility is an act of optimism. It presupposes that the world is worth inheriting and that one’s sacrifices will matter beyond one’s own lifespan. Societies marked by pessimism, existential anxiety, or loss of shared meaning consistently show lower fertility. When the future feels abstract, unstable, or morally unclear, people hesitate to bring new life into it.

Taken together, these forces explain why fertility declines persist even in wealthy, peaceful, and socially supportive societies. The issue is not ignorance or oppression, but incentive structures and meaning structures that no longer align reproduction with personal flourishing. Replacement rates fall not because people cannot have children, but because having children no longer fits cleanly into how modern life is organized or valued.