Introduction

In the first part of this series, we examined the idea that riches, ambition, pleasure, and knowledge must collapse before true transformation and realization can occur. In Part II, we drew from the examples of Gautama Buddha, King Ashoka, Augustine of Hippo, Leo Tolstoy, and Francis of Assisi, all of whom tasted wealth, glory, and prestige before coming to a decisive end of themselves. The reflection emphasized that fulfillment does not come through abundance or indulgence, but through an interior collapse of false securities.

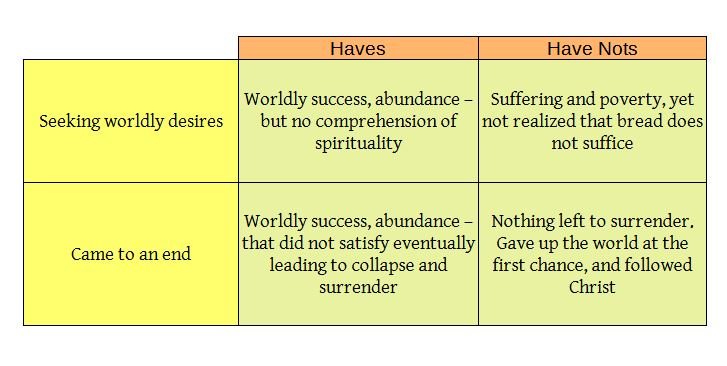

In this third installment, we turn to Scripture and attempt a more structured way of seeing these dynamics. We will employ a 2×2 matrix to classify the human condition in relation to desire, achievement, and the necessary end of self. On the horizontal axis we distinguish between the “Haves”—those who already possess wealth, power, or prestige—and the “Have-nots”—those who do not. On the vertical axis we distinguish between those who are still “Seeking their Desires” and those who have “Come to the End” of their pursuit. The resulting four quadrants are:

-

Haves + Seeking

-

Haves + End

-

Have-nots + Seeking

-

Have-nots + End

This framework allows us to interpret biblical personalities not merely as characters of history, but as paradigms of human longing and surrender. Each quadrant provides lessons about what it means to arrive—willingly or unwillingly—at the end of oneself.

The Matrix Explained

At the heart of this framework lies the question: What does it mean to reach the end of oneself? Some arrive by abundance, discovering that having everything still leaves them empty. Others arrive by poverty, finding that losing everything strips them bare before God. Some never arrive, always grasping for more. Others are humbled, often through suffering, and discover grace.

The matrix is not static. Human beings may move across quadrants during their lifetimes. The wealthy may collapse into humility, while the poor may continue to seek bread that perishes. Our hope is not to idolize one quadrant but to discern which direction leads toward the transformation that Scripture affirms: the relinquishing of self so that God may fill us.

Quadrant I: Haves + Seeking (Solomon)

The quintessential biblical figure of “Haves + Seeking” is King Solomon. Born into royalty, heir of David, and blessed with wisdom beyond measure, Solomon epitomized abundance. His kingdom overflowed with gold, cedar, horses, and alliances. He extended Israel’s influence to its greatest geographical reach. Yet, despite such grandeur, the record of his life reveals relentless pursuit.

Solomon sought wisdom, but wisdom turned into vanity. “I applied my heart to know wisdom and to know madness and folly. I perceived that this also is but a striving after wind”[1]. He sought pleasure, building palaces, planting vineyards, acquiring singers, concubines, and treasures beyond imagination. “Whatever my eyes desired I did not keep from them. I kept my heart from no pleasure”[2]. Yet, in the end, he declared, “All is vanity and a striving after wind”[3].

Why does Solomon belong to this quadrant? Because he had everything that men desire, and yet he continued to chase more. The riches did not quiet his hunger. The pleasures did not quench his thirst. His wisdom itself showed him the futility of it all. He represents those who live in abundance, yet cannot rest. The tragedy of Solomon is not that he lacked blessings, but that he sought meaning in them apart from God.

The lesson here is sharp: abundance without surrender does not end seeking—it amplifies it. Those who have wealth, prestige, and wisdom may be most tempted to believe they are fulfilled, yet they are often the most restless. Solomon’s conclusion in Ecclesiastes becomes the key: “Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the whole duty of man”[4]. Only when abundance is reoriented toward God can seeking cease.

Quadrant II: Haves + End (Nebuchadnezzar)

If Solomon is the restless seeker who never rested, Nebuchadnezzar is the king who was broken into rest. As ruler of Babylon, the greatest empire of his time, Nebuchadnezzar wielded unmatched power. His armies crushed nations, his city was adorned with the Hanging Gardens, and his pride was legendary. He stood on his palace roof and declared: “Is not this great Babylon, which I have built by my mighty power as a royal residence and for the glory of my majesty?”[5].

In that very moment, his downfall began. God humbled him, stripping him of sanity and sending him into the wilderness to live like an animal. “He was driven from among men and ate grass like an ox, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven”[6]. His humiliation lasted until he lifted his eyes to heaven and acknowledged the Most High. When his reason returned, so did his kingdom—but with it came a new confession: “Now I, Nebuchadnezzar, praise and extol and honor the King of heaven, for all his works are right and his ways are just”[7].

Nebuchadnezzar belongs to this quadrant because he was a “Have” who came to the end—not by his own choice, but by divine humbling. Unlike Solomon, whose end was philosophical, Nebuchadnezzar’s was existential. He literally lost his mind, and only in that abyss did he encounter God’s sovereignty.

The warning is clear: pride precedes collapse. To the Haves, the lesson is to recognize God before God must humble them. Yet the hope is also clear: even kings who exalt themselves can be restored when they lift their eyes to heaven.

Quadrant III: Have-nots + Seeking (Crowds for Bread)

On the opposite end are the Have-nots who Seek. Scripture gives many examples, but none is clearer than the crowds who followed Jesus after the feeding of the five thousand. Having eaten their fill of miraculous loaves and fish, they pursued Him across the sea, hoping for more. Jesus rebuked them: “You are seeking me, not because you saw signs, but because you ate your fill of the loaves”[8].

The Have-nots are those who lack material abundance, and understandably, they seek sustenance, security, and relief. The crowds’ yearning was genuine hunger, but their misunderstanding lay in believing that earthly bread was enough. Jesus lifted their eyes higher: “Do not labor for the food that perishes, but for the food that endures to eternal life”[9]. Yet many could not accept this, grumbling at His words.

This quadrant captures the desperation of humanity. Most of the world’s population lives here: striving, yearning, chasing after bread, security, and meaning. Their struggle is not one of excess but of insufficiency. And yet, like the crowds, they often miss the Bread of Life standing before them.

The lesson here is sobering: need can blind as much as abundance can. Poverty does not guarantee humility, nor does hunger guarantee openness to God. The Have-nots who continue to seek may remain in endless striving unless they recognize Christ as the true sustenance.

Quadrant IV: Have-nots + End – The Apostles Who Followed

If the previous quadrant celebrated figures of power and wisdom who came to the end of themselves after achieving much, this quadrant shines with a quieter glory. It is the quadrant of the apostles. They were not kings, nor philosophers, nor noblemen. They were tax collectors, fishermen, tentmakers—ordinary men with no titles to their names, no seats of power, no libraries filled with their writings, no thrones from which they ruled. In short, they were have-nots.

And yet, it is here that we see one of the most remarkable transformations in history. When Jesus walked by the Sea of Galilee and called, “Come, follow me,” they did not hesitate (Matthew 4:19). Peter and Andrew dropped their nets. James and John left their father in the boat. Matthew abandoned his tax booth. These were not men who had exhausted the glories of the world like Siddhartha Gautama or Ashoka; they had never possessed such things to begin with. Their power lay not in their résumé but in their response.

What makes this quadrant so profound is precisely that: they had so little to lose. When called, they simply went. They were not encumbered by palaces, armies, or manuscripts. The fishermen of Galilee and the tax collector of Capernaum had nothing that the world would envy, but they became the foundation of a movement that reshaped the world. Their willingness to obey without hesitation placed them immediately in the bottom-right quadrant—have-nots who had already reached the end of themselves.

The beauty of this quadrant is that it is accessible. Unlike the arduous journey of kings and philosophers who must first climb the mountain of achievement before realizing its futility, the apostles remind us that one does not need to ascend to great heights to encounter God. Sometimes, the greatest spiritual leap is taken not from a throne but from a fishing boat.

This quadrant reveals that the simplicity of obedience can rival the grandeur of any philosophy. When Jesus calls, the have-nots who respond find themselves already where emperors and sages spend a lifetime struggling to arrive—at the end of themselves, ready to be filled with something greater.

Movement Across Quadrants

The matrix is not destiny. People move across quadrants through choice, circumstance, and divine intervention. Solomon could have moved from seeking to end had he truly rested in God. Nebuchadnezzar was forced downward, yet restored. The crowds had the opportunity to move from seeking bread to receiving eternal bread but many turned away. Job and Paul stand as beacons of what it means to be at peace with God in deprivation.

The key question is: How do we move safely to the bottom right quadrant—Have-nots who have come to the end? The answer is not to seek poverty for its own sake, nor to despise abundance. Rather, it is to recognize that both abundance and lack can be idols. The goal is surrender: to see God as enough. For the wealthy, this means relinquishing pride. For the poor, this means lifting eyes beyond bread. For all, it means confessing with Paul: “I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord”[13].

Conclusion

The 2×2 matrix offers a simple yet profound way to interpret biblical personalities and human longing. Each quadrant illustrates the dangers and possibilities of abundance and lack, of seeking and ending. The hope is not merely to classify but to journey: from restless seeking, whether in wealth or want, to the peace of coming to the end in God.

This reflection is not the final word. It is one conclusion, one framework, one person’s interpretation of Scripture. Every reader remains free to seek, to question, and to discover for themselves. Yet the pattern of the saints and the testimony of Scripture converge: only when we come to the end of ourselves do we truly begin.

Footnotes

[1] Ecclesiastes 1:17, ESV

[2] Ecclesiastes 2:10, ESV

[3] Ecclesiastes 2:11, ESV

[4] Ecclesiastes 12:13, ESV

[5] Daniel 4:30, ESV

[6] Daniel 4:33, ESV

[7] Daniel 4:37, ESV

[8] John 6:26, ESV

[9] John 6:27, ESV

[10] Job 42:5–6, ESV

[11] Philippians 4:11–13, ESV

[12] Matthew 5:3, ESV

[13] Philippians 3:8, ESV